« previous 1 | 2

Censorship and Danger

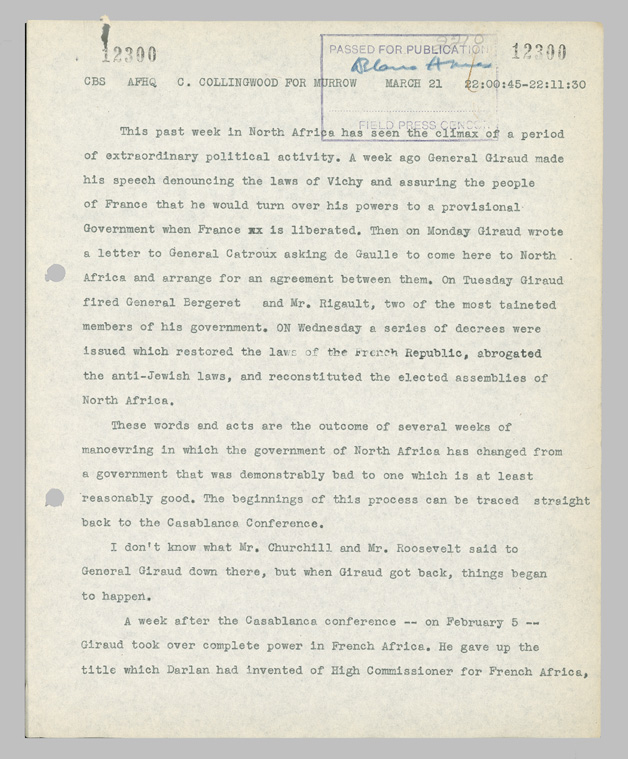

Like all correspondents, Breckinridge and others including Murrow himself, had to adjust their scripts to pass censorship, be they in England or elsewhere. Depending on the language skills of their censors and their own skill as writers, they were able to get out more or less of a story. Breckinridge admired Shirer, who adeptly forged sentences to pass the strict censors in Germany, e.g. when writing about Hitler's birthday: "A crowd of about 65 persons was massed outside the Chancellery."

Like all correspondents, Breckinridge and others including Murrow himself, had to adjust their scripts to pass censorship, be they in England or elsewhere. Depending on the language skills of their censors and their own skill as writers, they were able to get out more or less of a story. Breckinridge admired Shirer, who adeptly forged sentences to pass the strict censors in Germany, e.g. when writing about Hitler's birthday: "A crowd of about 65 persons was massed outside the Chancellery."

Breckinridge herself was masterful, however. Reporting about the Voelkische Beobachter, the official and most widely read newspaper of the National Socialist Movement in early 1940, the censors struck out one of her sentences about Hitler's and other's financial investment in the newspaper. But the censors left her last phrase uncorrected: "The motto of this important official paper is Freedom and Bread. There is still bread."2 In Germany, usually three but sometimes four censors - from the Foreign Office, the Propaganda Ministry, the Military and an additional one for a story on the women's movement - had to approve and stamp each script while "a technician sat at another [table] with a copy of my script and his finger on a button to cut me off if I departed from it in any way" as Breckinridge told decades later.

Even if correspondents managed to get their stories out and aired, listening to a foreign radio station such as CBS or BBC could be life threatening to German citizens and those from occupied countries. Shirer noted several such examples in his diary.

"February 4th 1940 … In Germany it is a serious penal offence to listen to a foreign radio station. The other day the mother of a German airman received word from the Luftwaffe that her son was missing and must be presumed dead. A couple of days later the BBC in London, which broadcasts weekly a list of German prisoners, announced that her son had been captured. Next day she received eight letters from friends and acquaintances telling her that they had heard her son was safe as prisoner in England. Then the story takes a nasty turn. The mother denounced all eight to the police for listening to an English broadcast, and they were arrested. (When I tried to recount this story on the radio, the Nazi censor cut it out on the ground that American listeners would not understand the heroism of the woman in denouncing her eight friends!)"

"February 4th 1940 … In Germany it is a serious penal offence to listen to a foreign radio station. The other day the mother of a German airman received word from the Luftwaffe that her son was missing and must be presumed dead. A couple of days later the BBC in London, which broadcasts weekly a list of German prisoners, announced that her son had been captured. Next day she received eight letters from friends and acquaintances telling her that they had heard her son was safe as prisoner in England. Then the story takes a nasty turn. The mother denounced all eight to the police for listening to an English broadcast, and they were arrested. (When I tried to recount this story on the radio, the Nazi censor cut it out on the ground that American listeners would not understand the heroism of the woman in denouncing her eight friends!)"

Shirer (1940), p288.

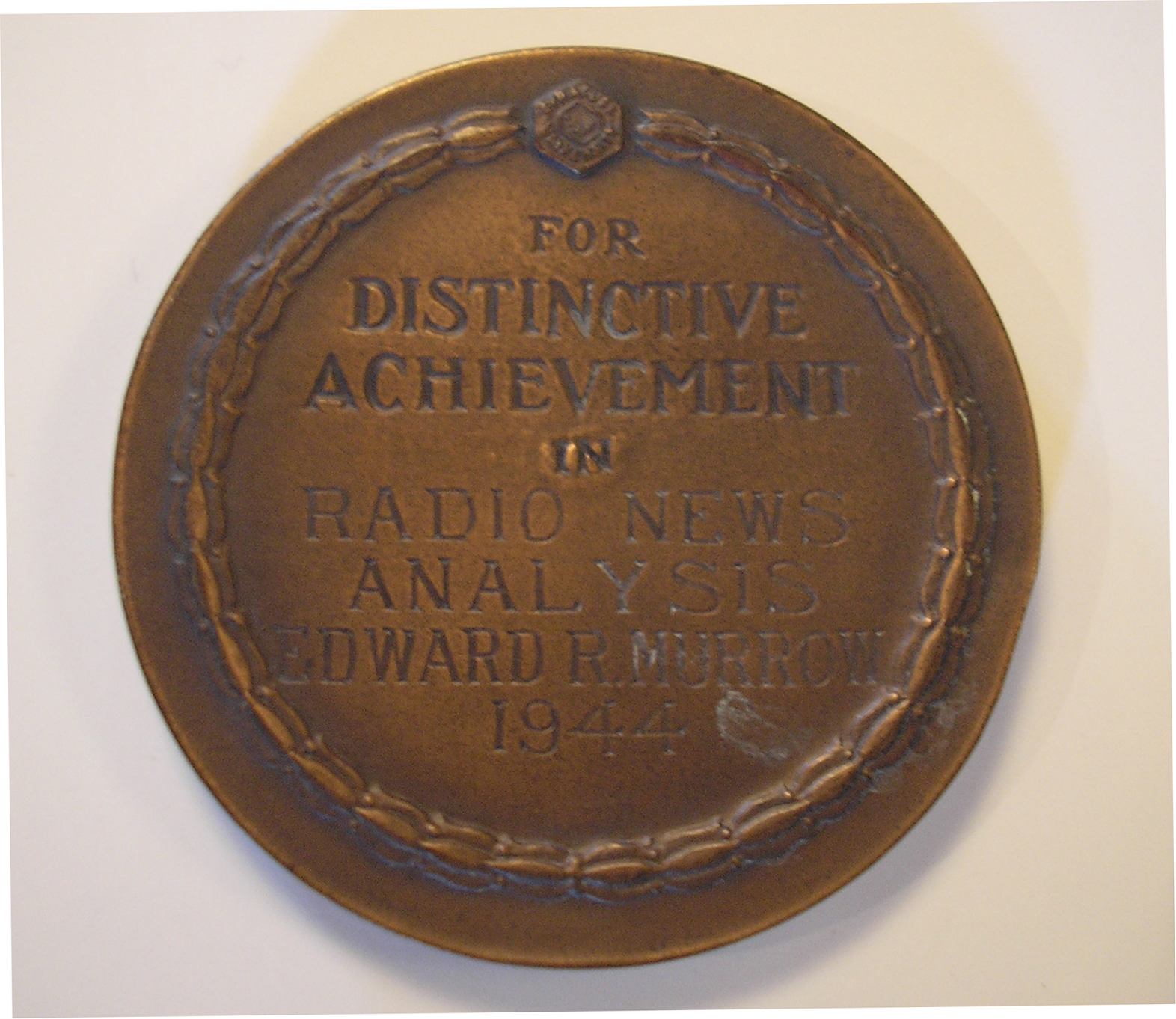

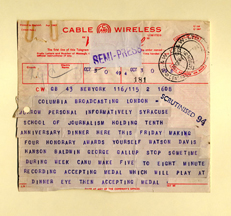

The work was dangerous as were the conditions under which it had to be done. Like other correspondents, Murrow's Boys barely managed to slip out of countries they had covered. They were thrown out by fascist regimes, were imprisoned, and lost family members (Lea Schiavi, a journalist and wife of Winston Burdett, was assassinated). They took part in bomb and reconnaissance flights, accompanied the Allied forces at innumerous fronts, participated in the invasion of Normandy, squabbled among and competed with each other, and still made up a memorable team of war correspondents. Murrow was well aware of this. He praised them liberally and ascribed his contribution to the field of journalism to their outstanding work; see here for example his acceptance speech for the Syracuse School of Journalism Award for Distinctive Achievements in News Analysis in late 1944.

Pages 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8Murrow did not interfere and seldom instructed the Murrow Boys on how to be a correspondent beyond the very general: to give the human side of the war, to be neutral and honest, to talk like him or herself, or to pitch the voice low. And herein lies Murrow's achievement: in having brought together this group of foreign correspondents and letting them do their work where they were at their best. Murrow's broadcasts were not necessarily better than theirs. Some wrote better. Some of Murrow's Boys had more subject knowledge and offered more trenchant analysis. They often worked under more dangerous and inconvenient conditions. They spoke the local languages. But in London, Murrow was centrally located, he was their boss, and he was a good coordinator. He elicited their good will and loyalty and gave both of these himself. He was very well-connected and his extensive speech training translated into a terse style and an excellent radio voice. Murrow knew how to use publicity, how to make himself look the role, and backed by CBS's efficient publicity machine, he thus became the iconic European news correspondent of World War II.

The Murrow Boys after the War

Reporting about World War II made Murrow's crew famous. After the war, Murrow would do much to help and support his 'Boys.' During his short stint as CBS Vice-President for News and Public Affairs, 1946-1947, he arranged top positions for those Murrow Boys still with CBS at the end of the war. This included Winston Burdett, Charles Collingwood, Bill Downs, Richard C. Hottelet, Larry LeSueur, Eric Sevareid, and Howard K. Smith. William L. Shirer had already returned in 1941 to work for CBS in the U.S. Many of the Murrow Boys would come together at least once a year in the 1950s to present the Years of Crisis television news round up consisting of in-depth analysis and commentary under the auspices of Murrow himself, and if necessary supplemented by other correspondents. A number of them wrote books about their war year reporting and experiences and became as influential as Murrow in the new medium of television.

2 Mary Marvin Breckinridge Patterson, "Radio Scripts by Mary Marvin Breckinridge 1939-1940 for the World News Roundup Programs of the Columbia Broadcasting System and 'Talk to Professor Higgins' Graduate Class: Broadcasting from Europe to America 1939-1940" at the School of Journalism of Boston University, Wednesday, December 1, 1976; The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA.

Credits

| Text and Selection of Illustration | Susanne Belovari, PhD, M.S., M.A., Archivist for Reference and Collections, DCA |

| Digitization | Michelle Romero, M.A., Murrow Digitization Project Archivist |

| Images | All images: Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA, Tufts University, used with permission of copyright holder. |

Partial Bibliography

For a full bibliography please see the exhibit bibliography section.

All documents from The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA.

Including:

Breckinridge Patterson, Mary Marvin, Radio Scripts by Mary Marvin Breckinridge 1939-1940 for the World News Roundup Programs of the Columbia Broadcasting System and 'Talk to Professor Higgins' Graduate Class: Broadcasting from Europe to America 1939-1940 at the School of Journalism of Boston University, Wednesday, December 1, 1976. January 15, 1940 Radio Broadcast number 9, 'Ice in Holland;' broadcast number 16, February 8, 1940, from Berlin, 'German Newspapers.'

Books consulted include Cloud and Olson (1996) in particular; also Persico (1988), Sperber (1986), and Kendrick (1969).

For Breckinridge, see also: Women Come to the Front: Journalists, Photographers, and Broadcasters During World War II, Library of Congress online exhibit, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/wcf/wcf0009.html

Briggs (all volumes).

Miall, Leonard, 'Obituary: Helen Kirkpatrick Milbank,' The Independent, January 8, 1998

Murrow, Edward R., Transatlantic Broadcasting, BBC Year Book, 1st proof, stamped December 10, 1942, in The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA; eventually published in BBC Year Book 1943 (Jarrold & Sons, Ltd., Norwich & London), Transatlantic Broadcasting, by Edward R. Murrow, p. 82-86.

Sevareid, Eric, Not So Wild a Dream (1946), p. 493-495. First edition in The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, including a dedication by Eric Sevareid: " For Ed, In memory of many things, Eric."

Shirer, William L., Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent 1934-1941 (Alfred A. Knopf: New York 1940), p288.

"William L. Shirer, 1904-1993," We Bring History to Life, http://www.traces.org/williamshirer.html

« previous 1 | 2

1 The eleven Murrow Boys were identified by Janet Brewster Murrow during her interviews with Stanley Cloud and Lynne Olson, authors of 'The Murrow Boys.' (1996) The origin of the term is unknown but is in use by the late 1940s.